Disclaimer: this is not legal advice, if you have a specific situation with legal implications, you should consult a qualified intellectual law attorney.

Table of contents

General overview on copyright

There are a multitude of factors and parameters that dictate who owns the copyright of an image, because it is a complex, largely circumstantial issue.

At its core, copyright protection in photography starts existing the moment an image is created. Postprocessing, developing or editing, and the chosen medium or equipment are irrelevant; as long as the image was freely and independently created, it is protected by copyright. As a copyright holder, the photographer is able to sell, adapt and display the work in any manner he sees fit, barring other contractual stipulations or circumstances.

A registration to a copyright office isn’t required and it isn’t necessary to mark the image with a notice or watermark. Copyright can only be transferred through a written agreement, which clearly outlines the terms and conditions of the transfer.

In circumstances that represent the photographer’s employment, such as working full-time for a company or being a freelance photographer for an agency, the contractual stipulations determine who owns the images. Usually, if the photographer is not the copyright holder he may still be able to use images as part of his portfolio, unless a non disclosure agreement specifically prohibits this.

Ownership of equipment doesn’t translate to ownership of any work created with that equipment, and this applies to reproductions as well, whether physical or digital. For example, when renting or borrowing equipment, the photographer who takes the picture remains the copyright holder of the photographs. Similarly, making images available in a book does not transfer the copyright to the reader. This principle also applies to digital services; using a cloud infrastructure for file sharing does not transfer the copyright to the service provider.

A fringe example is wildlife photographers setting up remote cameras to document wildlife: they hold the copyright even if they aren’t at the scene and didn’t trigger the shutter, as setting up the equipment is seen as an intention to take a photograph. An interesting controversy was the monkey selfie copyright dispute, which ultimately decided that the resulting images are part of the public domain. Even though the photographer set up the equipment and the monkey physically triggered the shutter, non-humans can’t hold copyright.

Copyright shouldn’t be mistaken with usage rights, as a photographer may grant a client or an organization a written license to reproduce his work in exchange for compensation. An exclusive license prohibits the photographer from using and selling the work in the capacity described by the license contract. Non-exclusive licenses allow the photographer to use the image in any manner, while the client receives publication rights.

Model releases

For any photographs that depict an identifiable person or group, a model release is required. It is a written legal agreement between the photographer and the model that establishes the conditions in which the photographs can be used. The photographer has an implicit moral obligation to the model, ensuring they aren’t depicted in an out-of-context or defamatory way.

An important condition of a model release outlines the intended purpose of the photoshoot, as it helps prevent later misuse. For example, if the photographer states that the images are used only for portfolio work, he isn’t able to sell these to be used in an advertising campaign before consulting with the model.

An exception would be editorial photography, where often a model release isn’t necessary, as such images have no commercial intent and are seen as contextual illustrations for the issues, events or information presented in an article.

Creative Commons

As a global nonprofit organization, Creative Commons continuously develops a platform offering copyright licenses that enable a standardized way to share creative work. They offer six options for licenses, each guaranteeing at least the possibility to share non-commercially, with attribution required. These licenses don’t apply to the photographer directly, as they retain full control over their work, but they establish a framework for the distribution of their work by other parties outside of those included in a contract.

CC BY (Attribution)

The most flexible license, allowing anyone to adapt, modify, and commercially distribute the work, provided the original creator is credited.

CC BY-SA (Attribution – Share-Alike)

This license permits the sharing and transformation of images as long as the author is credited and any copies or adaptations of the work are released under the same or similar license as the original.

CC BY-NC (Attribution – NonCommercial)

Any distribution or modification of an image under this license must be for non-commercial purposes but any derivative work doesn’t need to be licensed on the same terms.

CC BY-ND (Attribution – NoDerivatives)

No alterations are allowed with this license, but sharing of images is permitted even for commercial purposes, provided the author is credited.

CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution – NonCommercial – Share-Alike)

Sharing an image or its adaptations with this license restricts it to non-commercial purposes and requires any distribution to be under the same license.

CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution – NonCommercial – NoDerivatives)

The most restrictive license, allowing only non-commercial, non-derivative sharing with required attribution.

The organization also sets clear standards for each license type regarding the required information for proper attribution, purposes and exceptions. CC licenses are legally enforceable tools that provide clarity on what users can and cannot do with the licensed material. This framework helps creators protect their intellectual property while encouraging sharing and reuse.

CC0 (public domain)

While images in the public domain can be included in Creative Commons collections, they are not subject to CC licenses. Unlike copyrighted works, images in the public domain are free to use without restrictions, including for commercial purposes, without the need to obtain permission or pay royalties. If the author or source of an image in the public domain is known, it is still considered good practice to cite it. Once an image enters the public domain, it cannot be assigned a new copyright. It remains free for anyone to use, modify, and distribute forever.

In most of the world, unless otherwise stated, the maximum duration of a photography copyright is 50 years after the year of the death of the author. Once that happens, the works enter public domain and can be freely used. This stipulation and other related issues are dictated by the Berne Convention, which aims to protect literary and artistic works’ copyrights internationally, ensuring reciprocal recognition and enforcement. There are cases in which images can directly enter the public domain without needing to wait for the copyright to expire. Examples include images created for educational purposes or by certain government agencies.

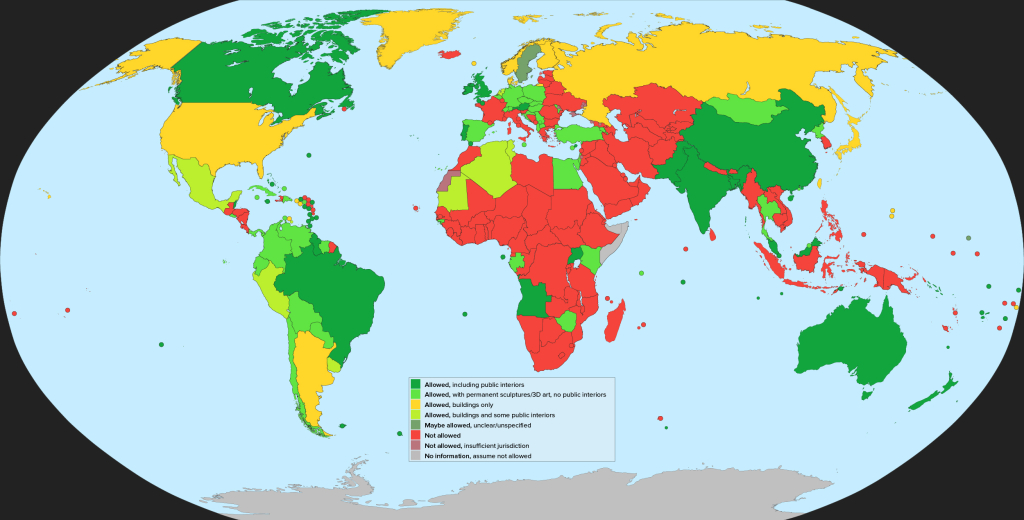

Every country has different copyright provisions, and when images are taken in a foreign country, the copyright laws of that country apply to the images. This means that photographers must be aware of the specific legal requirements and restrictions in each country they work in. This has implications, for example, concerning freedom of panorama.

Freedom of panorama

Each country has a different set of provisions regarding the freedom of panorama encoded into their copyright laws. It allows photographers to capture and publish images of buildings and public art without infringing on copyright and doesn’t include works in private space. In the United Kingdom, Canada, China, India or Australia, freedom of panorama extends to public interior spaces, while countries like France, Italy and South Korea heavily restrict their depiction of public spaces for commercial purposes.

In Germany, freedom of panorama is respected when the vantage point is on public property and the images are taken from at most eye-height, without the use of ladders, very high tripods, or drones. However, taking images with very long telephoto lenses that capture the inside of private property is strictly prohibited. These regulations aim to balance public accessibility to cultural and architectural works with the protection of private property rights and privacy concerns.

In countries where freedom of panorama in public spaces is restricted, commercial reproduction of architectural or artistic subjects may require a written permit from relevant authorities or copyright holders. This requirement ensures that the use of such images for commercial purposes respects the rights of the creators or owners of the depicted works.

This map presents the state of freedom of panorama as of December 2023.